FINANCE & DEVELOPMENT, December 2012, Vol. 49, No. 4

Developing countries can spend commodity windfalls on physical investment, but it may be better in the short run to distribute part of them to their citizens

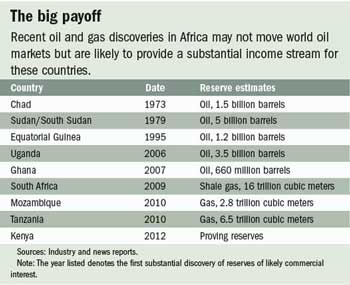

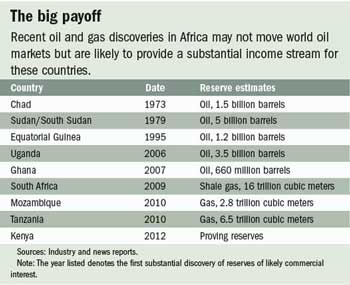

THE decade-long boom in commodity prices has boosted government coffers in many traditional producing countries. Following a wave of discoveries, new oil and gas producers—such as Ghana, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Uganda—are also emerging (see table). They may not all be major players at the global level, but the revenues they raise will be substantial for them and will brighten the prospects for growth and poverty reduction.

Still, the future is not without its dark side. New oil income will almost certainly relax constraints on government budgets, but it will also create challenges—as conditions in other resource-rich countries show. Many citizens of these countries remain poor, despite large revenues from resources. In some cases competition over resource wealth

has fueled or sustained civil conflict. Economic diversification is a further long-run challenge: nonresource sectors tend to lose competitiveness as a result of exchange rate appreciation.

All of these effects have been seen, for example, in Nigeria in past years. The long-run issues surrounding development become starker in light of the need to rebalance economies by fostering non-commodity-based industries to produce higher-value-added goods and provide a livelihood for people after commodity reserves are depleted. Advanced economies have moved away from natural capital—such as oil and gas deposits and mineral reserves—to physical and human capital (see Chart 1). But the wealth of poor countries tends to be concentrated in natural resources.

The traditional argument is that countries should use their resource revenues to finance public investment. But there are questions about whether this is always the best approach. The limited state capacity of many resource-based countries makes appropriate and effective investment difficult to achieve. Limited capacity reflects not only a government’s lack of technical ability to identify, implement, and monitor key investment projects. It is often also the result of public sector corruption that allows those with clout to misspend and misallocate the resource windfall, including through high-value construction contracts that are especially susceptible to mismanagement. As a result, in some cases sharply scaled-up public investment may be the wrong way to go. It may be more effective in the short run to distribute some of the windfall as a direct dividend to citizens and rely on their spending choices to create and foster nonresource industries. In the medium and long run, countries should beef up their governing capacity—investing in investment capacity, so to speak—to relax some of the constraints on the use of revenues.

Avoiding past mistakes

During the booms of the 1970s, many traditional commodity exporters embarked on ambitious, but often wasteful, public spending—including on infrastructure such as roads, ports, and railroads. Case studies document investment projects that were plagued by inefficiency and also contributed to resource misallocation (Gelb, 1988). Even when completed, large projects sometimes failed to provide benefits because governments were unable to cover the high costs of operating and maintaining them.

Commodity windfalls, because they move directly through government coffers, offer public officials ample opportunity to divert them for personal gain. Manipulation of public spending, especially in the letting of construction contracts, is a major impediment to the successful use of windfalls. A study of 30 oil-exporting countries for the period 1992–2005 shows that large oil windfalls cause a significant increase in corruption (Arezki and Brückner, 2012); this both raises the cost of public investment and reduces its quality. An index of the quality of public investment management produced by the IMF shows markedly lower quality in resource-exporting countries (Kyobe and others, 2011). In addition, spending booms triggered by oil revenues have often overshot available resources and led producing countries, especially those with weak institutions, to fall into debt (Arezki and Brückner, 2011).

To avoid such problems, commodity producers must take into account their institutional conditions when determining the long-term level and type of spending following a commodity windfall. We can model optimal spending decisions for countries with weak governing capacity by assuming that there are inefficiencies—due to poor governance and public institutions—that make the costs of public investment exceed its face value, and we can assume that those costs increase with the size of the commodity windfall. We can also consider the implications of a better or worse investment climate faced by private businesses, which will affect how strongly private investment responds to the opportunities created by public infrastructure spending. Different countries face different combinations of these two institutional conditions (see Chart 2). Some may have a relatively strong public administration but a poor business climate (for example, Algeria), while others with relatively low scores on perceived quality of state institutions manage to sustain quite an efficient private sector (for example, Kenya). We also consider an alternative to public spending: the direct transfer of windfall resource revenues to citizens to supplement their wage income and raise their opportunity to invest and consume.

Citizen gain

The direct transfer of resource windfalls to citizens has been done. The U.S. state of Alaska and the Canadian province of Alberta send their citizens a yearly payment based on oil revenue. Each Alaska resident, for example, received a dividend of about $1,300 in 2009 (Ross, forthcoming). Mongolia distributes part of its mining revenues to its citizens and has recently pledged to endow each Mongolian with a portfolio of dividend-yielding preference mining shares. One argument for citizen dividends draws on evidence that taxation has historically been central to the creation of effective modern states: by distributing resource revenues and then taxing back part of them governments improve public accountability because citizens are more inclined to monitor the use of public funds (Sala-i-Martin and Subramanian, 2003; Moss, 2011). More direct arguments relate to the observed inefficiency in public spending, especially as programs are scaled up, and the frequent failure of ordinary people to benefit from the scaled-up public spending programs. Still more immediate arguments relate to increasing evidence of the development impact of cash transfers and the possibility of making them effectively.

Social transfers work and are one of the most effective—and evaluated—mechanisms of development assistance, especially when those transfers are conditioned on actions by recipients—such as keeping children in school. Many studies document how such transfers help households reduce poverty and improve children’s growth indicators, encourage school attendance, and improve access to health services. There is also little evidence that transfers to poor people discourage people from working. On the contrary, recipients seem to use the money to search for jobs. Moreover, transfers appear to encourage productive household activity. Poor households are less constrained by the deficient credit and insurance markets that characterize less developed economies. Small but reliable flows of transfers have helped poor households accumulate private productive assets, avoid distress sales in bad times, obtain access to credit on better terms, and diversify into higher-risk and higher-return activities. There is also some evidence that the introduction of transfers into poor remote areas can stimulate demand and local market development. Transfers are increasingly being integrated into social protection programs. Evidence from many social programs suggests that resource-generated transfers can help both recipient households and the country.

Not long ago, it would have been difficult, if not impossible, to send a windfall dividend to citizens in poorer countries without much of it being lost or appropriated by corrupt civil servants. But new technology has opened up ways to transfer funds accurately and efficiently to households—and at low cost. Cellular phones and biometric smartcards are increasingly being used, even in countries with poor institutions and low capacity. For example, Pakistan’s Watan Card program delivered reconstruction support to more than 1.5 million flood-affected households. South Africa’s system of social grants effectively uses this technology, as does a program to support demobilized militias in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Biometric technology can overcome traditional difficulties in identifying recipients, preventing multiple payments, and eliminating “ghost” recipients. Gelb and Decker (2012) consider 19 programs. Not all programs have been comprehensively evaluated, but the evidence indicates that they can be implemented on a large scale with nearly all funds going for their intended use (“little leakage,” in economic parlance), using identification and payment technologies that provide benefits beyond the transfer program itself—such as access to a bank account for precautionary savings and fuller and accurate electoral rolls. Because these technologies can minimize the costs of distributing an oil dividend uniformly across the population, it is reasonable to assume that policymakers can use part of a commodity windfall to provide direct transfers at essentially zero cost.

What to do

Considering all these elements in a model of optimal windfall use leads to a number of conclusions that can help guide policy. All decisions should of course be made in a long-run context that encourages saving when resource income is high to enable spending to continue when that income is low. But beyond these considerations, institutional features shape how the windfall could best be used. Weaker public administrative capacity reduces the optimal level of public investment in favor of larger transfers to citizens: it is better to give private households part of the funds directly than to waste them on ineffective spending. Moreover, all else equal, a larger commodity windfall should induce lower rather than higher public investment, because the behavior of officials seeking to appropriate the windfall further weakens the country’s capacity. These conditions bolster the argument for transfers to citizens.

The underlying business climate also plays a role in determining the optimal use of resource revenues. Good conditions—such as security and stable pro-business regulations that encourage the private sector—may compensate for weak capacity and justify higher public investment. This is because public investment spending is likely to encourage more productive private investment, which in effect raises the return on the public investment. Government capacity may affect the business climate, but good governance and a good business climate do not always go hand in hand, as we show in our examples above. Commodity-producing governments and their strategic economic advisors must take these institutional factors into account when determining how to use their revenues.

Investing in investing

Limited government capacity is a constraint, but not necessarily a fixed one. Some countries—Chile, for example—have strengthened their capacity; others have arguably weakened it. A windfall might well be spent in part on improving a country’s capacity to manage its investment program and provide the key public goods and services—such as effective roads, power supply, and regulation—the private sector needs to thrive. To explore such a possibility we extended our basic model by introducing the possibility of reducing the adjustment cost in public investment over time—at a price. We found that optimal public investment increases over time, with reliance on transfers diminishing as ever-increasing public capital attracts more private capital and produces more wage income. In general, the better the business climate, the stronger the arguments for this strategy. There is less point in boosting public investment if it then fails to stimulate private investment to produce valuable output. More research is needed on modeling state capacity, ways to invest in that capacity, and the time frames for such improvement.

To combat corruption, commodity exporters could ensure better transparency in the handling of windfalls. For instance, the

Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative provides a global standard for transparency in the oil, gas, and mining industries, while the

Natural Resource Charter, which builds on the transparency initiative, offers more comprehensive principles for governments and societies on how to best harness the opportunities for development generated by extractive commodity windfalls. Those initiatives can serve as anchors for enhancing transparency and accountability in commodity-rich countries. More specifically, open publication of public procurement contracts can help improve investment quality and reduce contract costs and cost overruns (Kenny and Karver, 2012).

Countries can also boost their technical ability to identify and implement projects. An example is Chile, which for three decades has subjected all public projects to disciplined and transparent cost-benefit analysis. The South American nation standardized the approach to evaluating a project and separated the institution that evaluates a project from the one proposing it. The National System of Investments is based at the Ministry of Planning and is administered jointly with the Ministry of Finance. A combination of efforts to increase technical capacity and eradicate corruption is the best way to harness the power of commodity windfalls in developing countries. ■

Rabah Arezki is an Economist in the IMF Institute for Capacity Development, Arnaud Dupuy is Professor of Economics at the Reims Management School, and Alan Gelb is Senior Fellow at the Center for Global Development.

This article is based on the authors’ IMF Working Paper 12/200, “Resource Windfalls, Optimal Public Investment, and Redistribution: The Role of Total Factor Productivity and Administrative Capacity.”

References

Arezki, Rabah, and Markus Brückner, 2011, “Oil Rents, Corruption, and State Stability: Evidence from Panel Data Regressions,” European Economic Review, Vol. 55, No. 7, pp. 955–63.

———, 2012, “Commodity Windfalls, Democracy and External Debt,” Economic Journal, Vol. 122, No. 6, pp. 848–66.

Gelb, Alan, and associates, 1988, Oil Windfalls: Blessing or Curse? (New York: World Bank/Oxford University Press).

Gelb, Alan, and Caroline Decker, 2012, “Cash at Your Fingertips: Biometric Technology for Transfers in Developing Countries,” Review of Policy Research, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 91–117.

Heston, Alan, Robert Summers and Bettina Aten, 2006, Penn World Table Version 6.2,Center for International Comparisons of Production, Income and Prices at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia).

Ross, Michael L., forthcoming, “The Political Economy of Petroleum Wealth in Low-Income Countries: Some Policy Alternatives,” in Commodity Prices and Inclusive Growth in Low-Income Countries, ed. by Rabah Arezki, Catherine Pattillo, Marc Quintyn, and Min Zhu (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

World Bank, 2006, Where Is the Wealth of Nations? (Washington).

———, 2011, World Development Indicators (Washington).

has fueled or sustained civil conflict. Economic diversification is a further long-run challenge: nonresource sectors tend to lose competitiveness as a result of exchange rate appreciation.

has fueled or sustained civil conflict. Economic diversification is a further long-run challenge: nonresource sectors tend to lose competitiveness as a result of exchange rate appreciation.